Ripple chief technology officer David “JoelKatz” Schwartz moved to explain the gap between Ripple’s oft-touted roster of bank relationships and the still-modest on-chain activity on the XRP Ledger (XRPL), responding at length on July 30 to a widely shared thread of questions from investor and YouTuber Andrei Jikh. In a series of posts on X, Schwartz pointed to compliance realities, institutional behavior, and product roadmap items—most notably a forthcoming “permissioned domains” model—as key reasons that institutional flows remain largely off-chain today.

300+ Bank Deals, Little Volume? Ripple CTO Answers

Jikh’s prompt captured long-standing critiques: after more than a decade and “300+ bank partnerships,” why isn’t the XRPL clearing “billions in daily on-chain volume,” why would payers choose a volatile asset like XRP over stablecoins, and—in a world saturated with fiat-linked tokens—do bridge assets still matter? He also raised questions about tokenization strategy, including why a firm such as BlackRock would select XRPL rather than operate a captive chain, and about geopolitical risk for non-US users.

Schwartz’s central explanation for sluggish on-chain settlement was blunt about the constraints facing regulated entities that cannot unknowingly transact against illicit counterparties on public DEX liquidity: “Even Ripple can’t use the XRPL DEX for payments yet because we can’t be sure a terrorist won’t provide the liquidity for payment. Features like permissioned domains will address this.” The post acknowledged “it has been very slow” to shift institutional flows on chain, even as he argued that institutions are “starting to see the benefits.”

Pressed by another user on whether the same counterparty-risk problem exists on other L1s, Schwartz said that, depending on how features are used, “generally decentralized exchanges on public layer 1’s don’t give you any control or knowledge of who your counterparties are.” The point was procedural rather than moral—“regulations aren’t always totally logical,” he added—underscoring why regulated payment flows have struggled to route through open liquidity.

Schwartz framed “permissioned domains” as a design intended to keep the ledger’s openness while giving compliance-bound participants a venue with rule-enforced counterparties. In follow-ups, he described a structure in which “retail is welcome in the permissioned parts provided they can prove they’re not sanctioned,” and said the “net effect” should be that liquidity in these domains remains comparable to the open side because of market-making between the two.

XRP Vs. Stablecoins

On the stablecoin question, Schwartz rejected the idea that XRP’s volatility automatically disqualifies it for payments. He argued there are use cases where volatility “isn’t a minus, or is even a plus,” and—separately—contended that a functioning bridge requires inventory: “A bridge currency only works if someone is holding it so that you can get it precisely when you need it.” He added that if users don’t know which asset they will need next, they may rationally hold the “dominant bridge” because it’s cheaper to pivot from a liquid hub asset into whatever comes next.

Schwartz also addressed whether bridge assets still matter if stablecoins increasingly cover most trading pairs. He allowed that “if one stablecoin wins,” it could act as the bridge, but said he doesn’t think a single stablecoin can win because each is “only…stable relative to one particular fiat currency” and anchored to jurisdictions. That multi-stablecoin reality, he argued, leaves room for a neutral bridge to connect a “long tail” of tokenized assets.

Asked why a heavyweight like BlackRock wouldn’t simply build its own chain for tokenization—especially as some brokerages do—Schwartz downplayed the importance of chain homogeneity in a world of interoperability and portability. He urged skeptics to “ask the same question about Circle—why don’t they launch USDC only on their own blockchain?” implying the obvious answer: ubiquity and liquidity come from meeting users where they are, across many networks.

On geopolitics, he drew a line between XRPL, which he described as neutral infrastructure, and Ripple’s enterprise products, which are segmented by jurisdiction. “If you’re asking about XRPL, it’s not really US based,” he wrote, adding that the ledger “has never discriminated against any particular participant,” and conceding that, for Ripple’s own products, licensing realities apply and some corridors—“North Korea or Cuba any time soon”—are out of bounds.

Schwartz further argued that XRP’s role within Ripple’s payments stack remains material even if much of it is not visible on public ledgers. “I don’t have the numbers in front of me,” he wrote, “but I’m pretty sure XRP’s use as a bridge in Ripple Payments dwarfs every other asset.” In a related point on XRPL design, he reminded readers that “XRP has a privileged place on the XRP Ledger.”

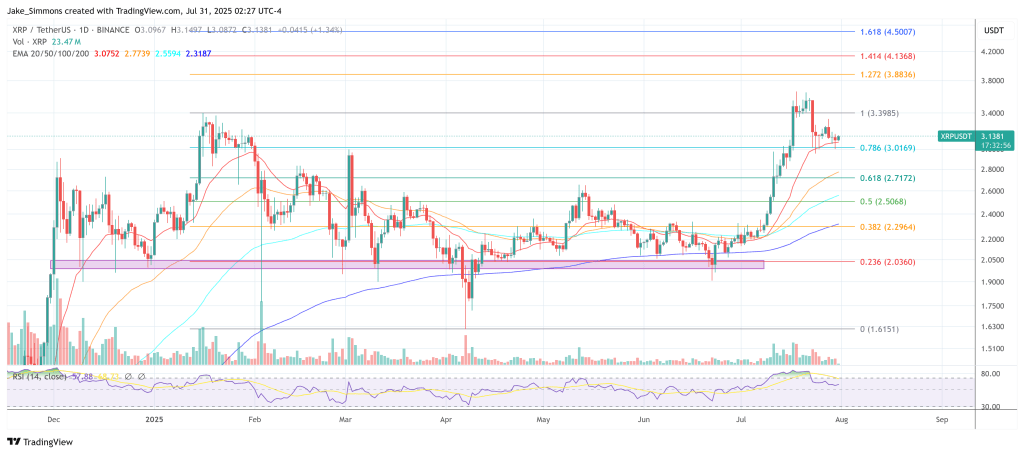

At press time, XRP traded at $3.13.